The modern science publishing industry operates much like turbo-capitalism — a system driven by profit maximization, consolidation of power, and resistance to regulation. What once served as a collective effort to disseminate knowledge has turned into a multibillion-dollar business controlled by a few dominant publishers such as Elsevier, Springer Nature, and Wiley. These companies have commercialized access to knowledge itself, transforming the public good of science into a high-priced commodity.

The evolution of the publishing system followed the classic pattern of enshittification. At first, science served the peers, then the users — offering access, visibility, and academic communication. Then publishers as peripheral service provider began to exploit those users to favor their paying institutional customers, tightening control over access and pricing. Finally, they turn on those very customers, extracting maximum profit while degrading service, fairness, and trust, until the entire ecosystem becomes a hollow structure of metrics and monetization.

Just as financial elites resisted government oversight, major publishers oppose reforms that would curb their profits. They lobby against open-access mandates, hide profit structures behind opaque pricing, and maintain control through prestige and impact metrics that entrench their market dominance. Their profits — often higher than those of Apple or Google — depend on free academic labor: scientists write, review, and edit for free, while universities must then pay to read their own work back.

Equity and fairness are collateral damage in this system. Article processing charges reaching thousands of dollars exclude poorer institutions and researchers from full participation. The ideal of open, global science is replaced by a tiered system where access and influence depend on wealth and affiliation.

Equally revealing is the industry’s attitude toward corrections and retractions. In a healthy scientific ecosystem, acknowledging and correcting errors is vital. But in the turbo-capitalist logic of publishing, retractions resemble market regulations — they threaten reputation, weaken brand value, and risk financial loss. Publishers therefore often delay or resist corrections, preferring to protect the façade of flawless output over the integrity of the scientific record.

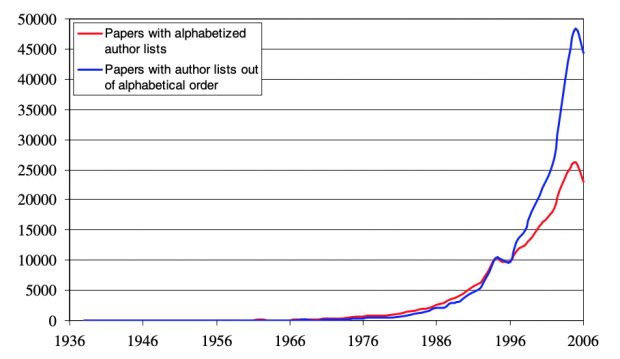

This distorted environment also shapes scientific behavior itself. Way too many self-assigned researchers, under immense pressure to build careers in a metric-driven system, quickly learn how to “game the system”. Even without proper training or deep experience, they chase citation counts, impact factors, and quantity over quality — optimizing for visibility rather than understanding. The system rewards the appearance of productivity, not the slow and rather uncertain process of genuine discovery.

Thus, the science publishing industry reproduces the same pathologies seen in unregulated capitalism: profit before accountability, personality show before truth, and career before fairness. In this turbo-capitalist model, we have learned the price of everything — but the value of nothing. To restore science to its purpose — the open pursuit of truth — it is not enough to call for open access. The entire system must be rebalanced away from speculative prestige and back toward collective responsibility, transparency, and genuine public knowledge.

(with chatGPT 5 support)

CC-BY-NC Science Surf

accessed 01.11.2025